Every single participant in the wine’s life cycle is bound by a similar goal—growers aspire to grow better fruit, winemakers want to craft a superior objet d’art and consumers want to drink better wine.

There are certain aspects of the winemaking process that are out of anyone’s control. Winegrowing at its core is farming. That means Mother Nature is fundamentally in charge. What the growing season brings to the sorting table is unmanipulated; but how about the rest?

There is an idealistic notion that winemaking is art; a pure process untainted by practicality. However, a closer look reveals that much can go wrong on the path from plant to bottle: weather events, pests, stuck fermentations, oxidation problems and many other issues can potentially plague a winemaker. Through the centuries of trial and error, vintners have fought a valiant battle to mitigate the devastating complications that can compromise an entire year worth of hard work.

With the onslaught of technology, they are now in a much better position to address these distressing matters. There are a number of powerful tools that aid in analyzing data and help vintners learn how they can make better wine.

One would think that California’s Napa Valley would greatly benefit from its proximity to Silicon Valley. However, the French are the leading innovators in wine technology. Companies such as Pellenc, Bucher Vaslin, Vivelys push the envelope in order to supply ground-breaking equipment.

The wine industry, as a whole, has been very slow to adapt to change, be it the winery tools or social media. One of the factors may be the plentiful access to highly trained and experienced labor. Many wineries employ crews of vineyard workers year-round, not just during harvest, or partner with viticultural management companies who have full-time staff. In France, innovation is spurred by a greater economic demand for automation due to higher labor costs.

The other “bonus” is the public perception of France’s winemaking reputation as being beyond reproach. Unlike their New World colleagues, they rarely have to wrestle with public or peer wrath over using non-traditionalist methods.

In the Vineyard – Vine Waterworld

Fruition Sciences, an Oakland, California startup founded by two French graduate students, has developed a system to measure the effects of irrigation on the vine. They apply sap-flow sensors to the plant in order to measure how much water is flowing through it. Powered by solar energy, the sensors transmit data in equal intervals, every few minutes. The system sounds an alert if irrigation is required. That type of precise feedback allows the viticultural team to implement real-time watering regimes.

During Harvest – The D-Day

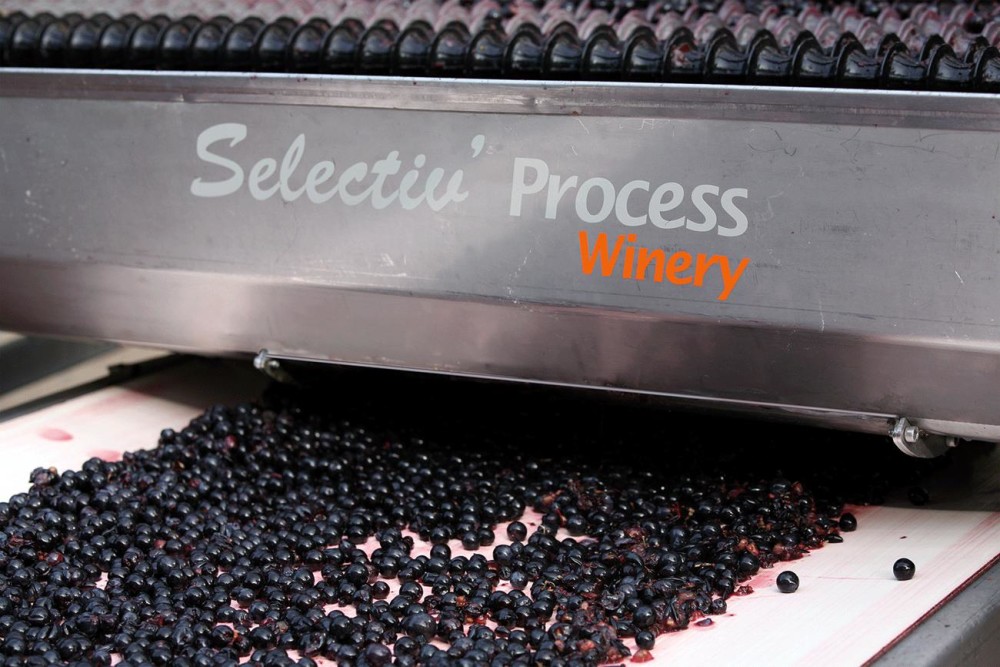

Producers of bulk wine have moved on from hand-picking decades ago. However, the practice has been shunned by high-end wineries for fear of negative consumer reaction. Some wine drinkers are unequivocally convinced that wine should be hand-harvested by farmers with little to no mechanical intervention. However, the stigma associated with automation is finally lessening, and several prominent producers have quietly adopted the technology.

One of the world’s leading producers of mechanical harvesters is the French firm Pellenc. Pellenc’s Selectiv’ System is not only a mechanical harvester, it also de-stems and has fruit-sorting capabilities. Waste items are left behind in the vineyard and no longer require attention at the winery. The containers come to the crush pad ready for mixing and pre-fermentation modifications. That frees up the resources that can be directed to the fermentation process. The machine has the capacity to harvest twenty tons of grapes overnight which would otherwise require several dozen workers.

In the Cellar – Truth or Dare?

One of the winemaking perils is premature oxidation, a condition that makes pink and white wines taste like oxidized apples.

A highly controversial wine-adjustment technology is reverse osmosis. In the late 1990s, in the wake of California Cult emergence, the industry trend took a curious turn. Some producers started picking fruit late in the season in order to make bigger, sweeter, more opulent wines that delivered pizzazz and that instant gratification. The unintended side effect of this practice was higher alcohol levels. To mitigate this, vintners turned to reverse osmosis. The smallest molecules in wine are water and alcohol. By passing wine through a casing with tiny holes, the compounds can be separated out. Then, only the water is returned to the vat, thus reducing the wine’s alcohol level.

Reverse osmosis is ardently criticized by purists who consider this type of manipulation objectionable. It’s hard to say how widespread it is, since most producers who use this process will not admit to it.

Closures – Is this Cardbordeaux?

A fully airtight screw cap is spurned by several countries governments, such Spain and Portugal who have been particularly vocal in their opposition and even passed laws prohibiting alternative closures. In addition, there are some wine critics and vintners who believe that a truly age-worthy wines requires some oxygen in order to mature properly.

There are several companies that attempted to address the issue. One of them, a pioneer in the field, Vinperfect, founded by a former Steltzner winemaker, makes a screw cap that contains an aluminum-coated plastic liner. This allows the winemaker to devise how much oxygen should leach through to bottle over time, while effectively eradicating any danger of TCA.

Sorting – This is the Berry You Are Looking For

Fraud Prevention – Bubble Bust

In the wake of recent criminal activity involving fine-wine fraud, some producers are determined to deploy technologies that ensure authenticity. One interesting approach is a “bubble tag” applied to the bottle’s label. Made by Prooftag, it contains a serial number and a unique pattern of randomly generated bubbles embedded in polymer, which can never be replicated, not even by the manufacturer. These type of tools ought to make both the winery and consumer breathe a sigh of relief when it comes to counterfeiting schemes.

Aging – To Barrel or Not to Barrel?

Traditionally, wines were aged in oak barrels, the oldest wine “technology.” However, barrel aging takes time and is very expensive, considering the average price per barrel is in hundreds of dollars.

Innovative aging technologies to the rescue. They involve maturing sur lie, micro-oxygenation and using wood fragments. Wood fragments or “chips” are often used in concert with steel of concrete tanks to infuse flavors ordinarily conjured via barrel aging. Micro-oxygenation can do wonders in accelerating the wine’s aging process. As a bonus, the practice sometimes improves the overall wine quality.

Preservation – Coravin Coup

Social Media – Savvy Consumers Take Charge

So What Does It All Mean?

Technology, in itself, does not necessarily improve wine quality. Instead, it gives vintners indispensable tools to make adjustments along the way. It is no substitute for fabulous fruit or wine making prowess. However, it allows vintners to decipher the process which often results in better wine.

Technology can contribute to the production of both inferior or superior wines. It is a highly useful tool, however it isn’t a substitute for human touch, taste, and intent. Winemaking is part science and part art, so it will always rely on an intuitive component.

Using sophisticated equipment, a winemaker could review in detail the wine’s fermentation records, and conclude that a heat spike somewhere in the process gave the wine great texture. However, given all the factors that go into making a final product, can they say with any degree of certainty that it wasn’t solely attributable to the vintage itself, field viticulture, vintner modifications…or was it all three?

Is a mechanical harvester a superior substitute to an experienced farm worker? How can one vineyard produce fantastic fruit while the one next door doesn’t? Can this variance be moderated by technical intervention? Is refractometer a worthy substitute for the winemaker’s palate? Measuring grapes’ sugar, acidity and pH levels is critical to the process, should such measurements be trusted to science over human perception?

The answers lie in one’s own mind. And heart. That’s what creativity is, staying true to your individual beliefs, desires, ethical standards and overall commitment. In the world of subjectivity, there are no absolutes.

We have seen how resistance to change artificially slows down the progress of technological applications to a centuries-old craft. Somehow the idea of man vs. machine, natural cork vs. synthetic closures just doesn’t feel “warm and fuzzy” enough for consumers to let go of the well-worn, familiar notions. In a way holding out at that last bastion of traditions is okay, since none of us can say assuredly that technology improves our wine.

The truth is—great wines are made with great technology. Or without.

If it was as easy as programming, it would be a predictable, preset product, not a labor of love.

With nine-thousand-year wine making history behind us, it seems that we are constantly discovering how little we actually know. Perhaps the inexplicable magic of winemaking is a mystery that doesn’t need to be scientifically solved.

As I sip on my glass of glistening wine jewel, I wonder what the wine world will look like in 3016? Perhaps vastly different, or may be more or less the same. A comforting thought, I admit.

You must be logged in to post a comment.